Breakfast

Grant Burkhardt

Letter from the Editor

Dear Reader

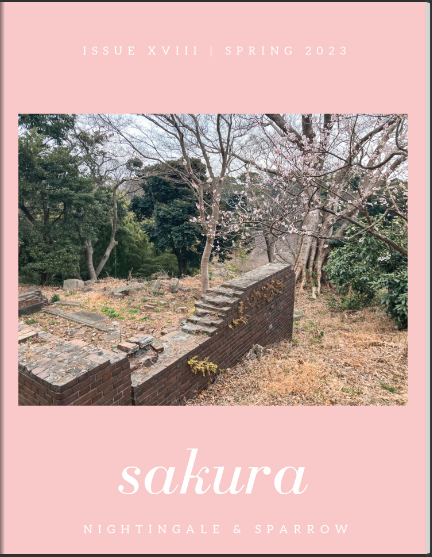

Welcome to the enchanting world of sakura! As we unveil our latest issue of Nightingale & Sparrow Literary Magazine, we invite you to immerse yourself in a realm of delicate beauty and ephemeral wonders. It is with great joy that we present our eighteenth issue, marking yet another milestone in our journey.

For this issue, we asked writers to capture the essence of sakura—the pink and white world where everything feels delicate and fleeting. We sought stories “about a moment of fleeting beauty, a memory that lingers like the sweet scent of sakura.” And oh, dear readers, the responses we received were nothing short of breathtaking.

Within these pages, you will discover tales that encapsulate fleeting beauty, moments that leave an indelible mark on our souls. Love and loss intertwine in narratives that resonate deeply, while quiet realizations about the passage of time gently unfold. Our talented contributors have masterfully harnessed the power of sakura to transport you to a realm where beauty and transience coexist.

As you delve into the tender tapestry of words and emotions we’ve curated for you, you will encounter mesmerizing pieces such as “At the Edge of Hope” by Kersten Christianson, “Sweet Sorrow” by Jennifer Geisinger, and “Seattle Sunrise” by Lindsay Pucci. These captivating works invite you to reflect on the fragile nature of existence and the profound impact of fleeting moments.

Before bidding you farewell, we would be remiss not to express our gratitude to those who have helped bring this issue to fruition. Each contribution, whether through submitting their work, supporting us behind the scenes, or simply being a devoted reader, is invaluable. Nightingale & Sparrow continues to thrive because of the unwavering dedication and passion of our global community of creators.

Wishing you moments of ephemeral joy through sakura and beyond.

Juliette Sebock

Editor-in-Chief, Nightingale & Sparrow

In the leadup to our eighteenth issue ’sakura’, we shared a series of micropoems from our talented submitters:

ISSN 2642-0104 (print)

ISSN 2641-7693 (online)

Founding Editor, Juliette Sebock

Breakfast Grant Burkhardt

The gravity of tenderness Karen E Fraser

Neighborhood Ed Brickell

Iris Robert Rice

Frederick the Night Blooming Cereus Valerie Hunter

Mother, Sister, Daughter, Sakura Vikki C.

for Now Tylyn K. Johnson

Sublet Emily Kedar

At the Edge of Hope Kersten Christianson

Final Measure Ellen Malphrus

A Strong Man Jennifer Mills Kerr

Sweet Sorrow Jennifer Geisinger

Visual Art

Early Blossoms in Spring 2 Jacelyn Yap

Early Blossoms in Spring 3 Jacelyn Yap

Early Blossoms in Spring 4 Jacelyn Yap

Seattle Sunrise Lindsey Pucci

Cover Image

Early Blossoms In Spring 1 Jacelyn Yap

In the leadup to poetry, we shared a series of micropoems across social media:

Poetry Contributor

Vikki C., author of ‘The Art of Glass Houses’ (Alien Buddha Press), is a British-born writer, poet and musician from London, whose literary works are informed by existentialism, science, the metaphysical, and human relationships. Her poetry and prose have been published or are forthcoming in Across The Margin, Black Bough Poetry, Acropolis Journal, DarkWinter Literary Magazine, Spare Parts Lit and others.

Jennifer Geisinger

Violet watched the tree all year. She was going to miss it when she left. It would be good to cash in, cash out, sell the house, have enough to retire, enough to live on. She didn’t need the headache anymore. It was hard to take a ferry every time she needed to see a doctor, go to chemo or radiation, even though the visits were fewer and farther between. She hated having to put anyone out. It took an entire day sometimes, just to go for a check-up, and the ferries were always late. She fantasized about calling an Uber, of being anonymous. She was becoming so practical in her old age.

Violet wasn’t old. Old enough, though, to not want to pay someone all the time to keep up the lawn, to keep up appearances, to chat at Thriftway, to watch all the new children come through town and have no idea who they were. Her own two couldn’t believe she was selling — a wave of hurt, betrayal. Hurting her kids was enough to make her turn back, to take it all back, to just stay and stay and stay, just in case they decided to return home.

But they couldn’t come back, and shouldn’t come back, and she couldn’t just spend her whole life waiting.

This island was a trap, it really was. It caught her with its beauty, with the strangeness of explaining to people about island living without sounding too proud, too much, too elite. It was hard to explain that she wasn’t one of them, not one of the mansion people, or the summer people. Just an islander. She wasn’t really an islander though, and would never say that around a local. Unless your family had been homesteaders that came before the ferry system, you couldn’t claim that title. Everyone was a newcomer until maybe the twenty-year mark, then you could say you’d been there for “a while.”

Still, she was glad to go, isn’t that strange? She had wanted to move here for so long, and anytime she was away she longed for it, with a longing that she had accepted would always be there, whether or not she was on the island. It squeezed her heart so tight with love, it almost felt like a straightjacket — constricting, taking away her free will, taking away all her choices of love, travel, retirement, excitement. She wouldn’t be happy staying, and she would always regret going. She knew this to the marrow of her bones. She knew it even as she could feel her house falling apart. She was glad the carpenter ants she had held at bay for twenty years would soon be somebody else’s problem, along with the hairline fracture in the foundation, which would only be forgiven because it was a seller’s market. Life on an island is always a seller’s market, because love is blind.

She was glad to leave when the tree was in full bloom. It was prettiest this way. All year it worked toward the big show. She always said they should name the cherry tree. Her children spent half of their childhood climbing it along with all the other children from the neighborhood, long before she had come, and hopefully long after she was gone.

For a few years, her daughter had called the tree Sweet. She would croon to it, and sing “Sweet, Sweet, Sweet,” in the tuneless lullabies of children, which are brand new, but hauntingly familiar. It was just one cherry tree, but it was her favorite part of the whole thing.

She had gotten through the horrid good-bye parties, and promised to visit, knowing deep to the quick that she would not. She would not visit again. It was time for good-bye, the very last one. Even though she knew she could fall, and what a disaster that would be, she went up the little hill in her yard, where the tree lived, and supported her whole self with the trunk. She enveloped herself through the branches, and leaned hard into her, something she realized she had never done in all the years she had watched the flowers bloom and die over and over.

She told the tree to be good, just as she did her toddlers when she left them with a sitter, and breathed in the freedom of a quick getaway. She gave the tree a last little pat, and she hoped it would live and last. Sweet. She realized that she was talking to a tree, but nobody could see her, and if they did, they would understand. She had given so much, and had meant so much.

It was time to go. The hurt became intolerable. It would fade if she could just get on the boat. Thirty years, in and out. Everything else was already gone, already stored, the house ready for the next chapter. She got in her car and drove away from her dream and headed to the ferry dock.

Jennifer Mills Kerr

Summers, our bikes leaned against the front porch; winters, our boots piled in heaps by the door. Chris and I couldn’t wait for his mom’s pancake breakfasts on Saturdays. Mrs. Riley was a round woman, freckled, cheerful. I was eleven when she died; an accident, everyone said, nothing more.

Soon afterward, Mr. Riley moved the family away — though he refused to sell the house. None of us knew why.

Now 34 Edgefield Road remains, sinking into the earth, dilapidated, forlorn. This morning, I watch sparrows fly in and out of its broken windows. Do they sing inside those empty rooms?

No sound except the sigh of wind through the elms, dappled light, a golden murmur around my feet. I imagine the tiny birds chirping inside the house with its creaking floors and scent of dirt, of rot — I can see it so very clearly — but if anyone invited me inside, would I go? Where’s Chris now?

I haven’t told my wife how frequently I come here since Arthur died. We still have Susan, of course: a promising girl, very different from her brother. Art came into this world burdened by melancholy. There was nothing I could do to change that. Sharon and I tried, but our son was just too heavy for us to carry. And I’d always imagined myself a strong man.

They found Art in his dorm room. Where he got the pills no one could say. Or would.

My heart, banging inside my chest as if to break loose. What was it Mrs. Riley always said? Let me get you a drink, sweetheart. You look spent. Iced tea, sweet and tart and cold. She’d watch as I gulped it down. There, now.

Suddenly, a sparrow appears from inside the house — though it doesn’t fly free. Instead, it perches upon one window’s jagged glass, preening, flickering its wings. There, now.

I wait. Not for the creature to sing, but to watch it fly, to a tree or into the light, anywhere, anywhere else. I’ve got to see.